Resilience

To become a resilient society, we need to become the heroes and protagonists of a different story. Who are we? We are a builders collective. We are building leaders to design a resilient society.

Design for Resilience: A Designlab Webinar

Learn how to design for resilience with Designlab Mentor Stephen Bau.

- What is resilience?

- What is the role of the designer?

- How can we gain permission to ask better questions or to think about the bigger picture?

- How can we better understand the stories we tell ourselves and, perhaps, tell better stories?

- How do we prototype for resilience? How do we imagine, design, and build the future together?

Design for Resilience with Stephen Bau

Here is the slide deck referred to in the presentation. Below are the notes prepared for the Designlab Webinar.

Humans are unique in their ability to tell stories. As designers, we are trained in the art of storytelling, though we tend to use the visual language of imagery and typography.

As a designer who has been working professionally since 1988, I have a few stories to tell.

But, I am going to tell you a story about resilience. It’s the story that we are all engaged in right now, during a global pandemic and financial crisis, as we discover how resilient we are when faced with unexpected changes in our usual habits and routines. Many of us are facing the collapse of everything we once knew and are trying to adapt to a new reality. Others are facing their own mortality. Others have, regretfully, lost their lives. So many things are out of our control.

In areas where we do have agency, it matters how we respond. It’s times like these when we discover how well we can bounce back from adversity. Will we bend under the pressure, or will we break?

I have been hearing the term “resilience” a lot these days. I have been finely tuned to notice, especially since I named my business in 2015. But I’ll get to that later.

My interest in resilience goes back to the beginnings of the Bauhaus in April of 1919. I was 50 years old when the Bauhaus turned 100 last April.

I have been obsessed with the Bauhaus for a long time. I called my first business, Bauhouse Visual Communications in 1991, because my last name is Bau, and I was working in an attic over the garage of my parent’s house.

When the internet came along, I tended to be an early adopter of technologies. I could have bought the domain, bauhouse.com, but I wondered if it would be a good idea to always be spelling out my domain name to keep it from being confused with the famous design school. Instead, when I realized that a domain squatter had snapped up bauhouse.com, I registered bauhouse.ca, and ever since, I have been known by this avatar on most platforms.

I was still a little uneasy about using “Bauhouse” as my business name, so I tried to think of something else. What would Walter Gropius, the architect who started the iconic German design and architecture school, call the school if it had started where I live in Vancouver, Canada? (Well, Abbotsford, actually—about an hour east of Vancouver.) What might we name a school of design that was a socialist, utopian collective of craftspeople, artists, sculptors, painters, and architects?

My last name, Bau, is Chinese. But in German, the word means “to build.”

So, I decided on the builders collective. Of course, it should be in lowercase letters, since that is one of the rules Herbert Bayer decided when considering ways to reduce the complexity of typographic design and production. The philosophy of the modernists was to get rid of any superfluous ornamentation.

Everything was reduced to bare essentials:

- black white grey

- blue yellow red

- circle triangle square

- sphere cone cube

- steel glass concrete

There was no need for serifs on typefaces, for example.

I didn’t like the idea of having such a long email address: stephen@builderscollective.com.

Maybe I could find a way to shorten it. I searched for builders without any vowels. I found bldrs.co. Then I realized I could turn BLDRS into an acronym: “building leaders to design a resilient society.” So, I incorporated as BLDRS Collective Inc.

The New Basics

Ellen Lupton and Jennifer Cole Phillips wrote a book about how we might reintegrate the philosophies of Bauhaus pedagogy into the methodologies of modern graphic designers in the age of digital production. They called it, Graphic Design: The New Basics.

As UX designers, we are drawing on these basic principles of modern design that have been honed over the past 100 years since, as some might argue, the graphic design profession was practically invented at the Bauhaus.

The Bauhaus movement was about rebuilding society from the ground up, since the world had been devastated by the First World War and the Spanish flu.

- Why World War I Ended With an Armistice Instead of a Surrender

- World War One’s role in the worst ever flu pandemic

The monarchy was abolished, and Germany was dabbling in its first experiment with democracy in the Weimar Republic. The Bauhaus school was part of the experiment to break down the barriers between the elite academic fine artists and the working-class craftspeople who made the objects of everyday life.

However, in time, the political environment of Weimar became hostile to the liberal influence of the Bauhaus, so Walter Gropius designed the building of the future, as a model of a modern educational environment, combining the diverse functions of daily life into a synergistic whole. The Bauhaus moved to Dessau in 1925, and the new building was inaugurated in late 1926. The asymmetrical geometric forms of the building showcased a daring architectural style, featuring curtain walls of glass that are cantilevered in such a way that they seem to float out and above the concrete foundations. The rectilinear forms of the exterior exposed the functions of each interior space, rather than present a classical, symmetrical façade that concealed the building’s inner workings. The industrial materials also served as a more economical and efficient structural support for the modern building: steel, glass, and concrete.

The Bauhaus was an experiment that lasted only 14 years, before the Nazis closed the school in Dessau in 1931, regarding the products of the school as “degenerate art”. After an attempt to reopen the school in a rented building in Berlin, the Nazis shut it down in April 1933.

However, the students and masters, the diaspora of the Bauhaus, spread around the world to places like Japan, India, Israel, Britain, France, and the United States.

- Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer at the Harvard Graduate School of Design in Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina

- László Moholy-Nagy at the New Bauhaus in Chicago

- Herbert Bayer at the Aspen Institute in Aspen, Colorado

The Bauhaus became known for its influence in modern graphic design, furniture design, ceramics, textiles, and architecture.

In that way, the story of the Bauhaus is about the resilience of its artists, designers, and architects to spread the ideas and approach of the school and transform the way we learn about and practice design to this day.

The Crisis

At the beginning of this year, the world woke up to a crisis. We have been discovering the meaning of resilience by observing how we respond to the crisis.

- A pneumonia of unknown cause detected in Wuhan, China was first reported to the WHO Country Office in China on 31 December 2019.

- The outbreak was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020.

- On 11 February 2020, WHO announced a name for the new coronavirus disease: COVID-19.

World Health Organization: Rolling updates on coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

What is resilience?

A good way to understand a term is to think of its opposite. The opposite of resilient might be brittle or fragile. A rubber ball will bounce back. But a dry twig will snap.

Resilience is strength in the face of adversity.

As Judith Rodin defines it in the subtitle of the book she published in 2014, The Resilience Dividend, resilience is “being strong in a world where things go wrong.”

Resilience is the capacity of any entity—an individual, a community, an organization, or a natural system—to prepare for disruptions, to recover from shocks and stresses, and to adapt and grow from a disruptive experience. As you build resilience, therefore, you become more able to prevent or mitigate stresses and shocks you can identify and better able to respond to those you can’t predict or avoid. You also develop greater capacity to bounce back from a crisis, learn from it, and achieve revitalization. Ideally, as you become more adept at managing disruption and skilled at resilience building, you are able to create and take advantage of new opportunities in good times and bad. That is the resilience dividend. It means more than effectively returning to normal functioning after a disruption, although that is critical. It is about achieving significant transformation that yields benefits even when disruptions are not occurring.

In the twenty-first century, building resilience is one of our most urgent social and economic issues because we live in a world that is defined by disruption. Not a month goes by that we don’t see some kind of disturbance to the normal flow of life somewhere: a cyber-attack, a new strain of virus, a structural failure, a violent storm, a civil disturbance, an economic blow, a natural system threatened. Yes, the world has always known disruption, but there are three disruptive phenomena that are distinctly modern: urbanization, climate change, and globalization.

The world’s population is more rapidly urbanizing than at any time in human history, forming into highly concentrated urban and metropolitan areas, some of truly astonishing proportion both in terms of population and geographic size. Cities are extraordinary and wonderful places, yet their growing populations and increased density make them newly vulnerable to disruption, crisis, and disaster in many ways. They are more susceptible to weather and climate-change threats, because, as they grow, buildings and structures are often developed in areas that are more vulnerable to hazards. They are more in danger of systems dysfunction because infrastructure is inadequate, nonexistent, or poorly maintained. They are more likely to experience rapidly spreading disease outbreaks because of the close contact of shifting populations and insufficient health-care facilities. Economic systems are burdened, governance structures are strained, and social cohesion comes under stress. What’s more, the expansion and further development of urban areas typically affect ecosystems, the natural systems that are fundamental to human resilience, so the impact of urbanization is almost always a social-ecological one.

…

These three factors are intertwined and affect one another in a social-ecological-economic nexus. Because everything is interconnected—a massive system of systems—a single disruption often triggers another, which exacerbates the effects of the first, so that the original shock becomes a cascade of crises.

I think the best way to think about the topic of resilience is to imagine the everyday, mundane moments of life as part of a larger story.

There is no one in this life who has been able to avoid the frustrations, anxieties, loss, pain, and grief that is an inescapable part of the experience of being human.

As user experience designers, we learn to be observers of human behaviour, and to notice the frustrations, pain points, and problems when people use products.

Norman Doors are a classic example. If someone sees a door handle, there can be some ambiguity about which way the door opens and whether we are supposed to push or pull. This is how we might first learn about the problem of poor design.

In Designlab, we are helping people learn the philosophy, the empathy, the tools, and the skills to better understand how to create products that solve human problems. We can uncover latent business opportunities to improve products by observing when things go wrong.

It is through failure that we learn what works. We learn to walk by crawling, then toddling, falling, and getting back up again. We discover balance by working against the natural forces of gravity by using our sixth sense of equilibrium to avoid the pain of falling.

And you thought we only had five senses! The ear contains the sensory apparatus for both hearing and balance. Without a working vestibular system, we cannot stand upright.

A Definition

Resilience is the awareness of our limitations and the challenges that we face and the ability to recognize our responsibility to engage our perceptions, cognitions, emotions, and actions in the world as creative problem-solvers and agents of change.

What is the role of the designer?

The dramatic irony facing the design profession is coming to a climax with the realization that we have painted ourselves into a corner. By making our living on being the spokespeople for the leaders of corporate capitalism, we have come to fill the role that is analogous to that of the priests of ancient empires. Priests held the knowledge of the mysteries of cryptic symbol systems and the legacies of meaning hidden in images, symbols and written language. The interpretation of these sacred texts were limited to the literati, a select few who had the time and the resources to expend on learning to read and write and to glean from the wisdom of the ancient sages.

The democratization of literacy, technology, currency and agency have opened the doors to opportunities that could never have existed without the accomplishments of those who came before, and we find ourselves in new, uncharted territory. Yet, we have received an inheritance that threatens our survival. We are discovering that the institutions of education, government, law, business, industry, media, and military are based on centuries-old assumptions and biases that do not lead to human flourishing, but rather an increasing inequality that supports extremes of excess on one hand and oppression on the other. One universal symptom of the trajectory of our global activity as humans has been our tendency to feel less human. By that, I mean that the mental health struggles that we face are pervasive across the spectrum of human experience.

Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis

A philosopher named Hegel suggested that there are not only two sides to every problem. There are three. Two ideas are in conflict, but a third idea resolves the conflict.

As designers, we tend to observe dialectically opposed viewpoints and search for ways to discover the synthesis that brings ideas together to create something new, innovative or original.

Our methods as user experience designers is to integrate research into our process. We observe in order to understand. We seek to understand in order to explore possible solutions to problems. That, to me, is the essential role of a designer.

That role is not necessarily confined to the work of professionals. I would hope that the approach of design can be the aspiration of the human project. We are resilient creatures with the capacity to use our minds to solve problems by creating tools that enhance our inherent abilities.

Marshall McLuhan wrote a book in 1964 called Understanding Media: Extensions of Man. He defined technologies as extensions of our abilities. A hammer is an extension of our hand and arm, increasing the force that we can exert on another object. The wheel is an extension of our legs and feet, increasing our mobility. These tools have the effect of enhancing our abilities, but numbing them at the same time. We outsource the work that we need to perform to tools that enhance our natural abilities.

The computer is an extension of both our rational, analytical minds and our emotions and limbic systems. We have outsourced our memories to machines, so we can retrieve the world’s knowledge by typing a search query. We can also broadcast our thoughts and emotions across vast distances. It is now possible to broadcast fear and anxiety around the world and shutdown global economic systems in response to our fear of death.

As designers, we make tools. We shape our tools and thereafter our tools shape us.

Powers of Observation

“The power of the arts to anticipate future social and technological developments, by a generation and more, has long been recognized. In this century Ezra Pound called the artist ‘the antennae of the race’. Art as radar acts as ‘an early alarm system,” as it were, enabling us to discover social and psychic targets in lots of time to prepare to cope with them.

Filling The Gap

According to Marty Neumeier, design is the gap between vision and reality. You have a vision of how the world could be better. Design is the application of the scientific method to the process of creativity. The design artefact is not the product. The real artefact is the result:

- to know truth,

- to create beauty,

- and to do good.

Things Break

Resilience assumes that things are not what they could be, that things go wrong. But we have agency; we have opportunity; we have abilities; and we have each other.

But that is where things have gone very wrong. We live according to narratives that put other people in categories that we believe are in opposition to our own personal and social identities and welfare. We divide over race, creed, gender, shape, economic status, political affiliation, geography, and a plethora of differences.

The importance of finding a common narrative of our origins is to discover what we have in common as human beings and to give us reasons to consider our common life together on this planet. This is the only place that we are currently aware of in this universe that has the unique characteristics to sustain life. There are so many other forms of life that we are living with. We are all neighbours. The essential truths that were taught to me when I was a child was to love our creator and to love our neighbours. That message still resonates years later, even if I have my doubts about how we received these sacred texts, whether they were divine revelations or human inventions.

The Human Project

We are having a hard time understanding exactly what we should be doing, because we are having a difficult time figuring out what our role as designers should be in this effort.

We are looking for role models, and there are some inspiring voices. Ideas about what it means to form a resilient society are coalescing. The technologies are evolving to create opportunities for real transformation.

Next comes the difficult and exciting process of observing, listening, visioning, and creating that can lead to a cooperative and collaborative project of caring for our world and for each other. That is the human project.

We all have a common origin on this planet and we all share a common destiny on this planet. The priority should not be “the economy.”

What is “the economy” anyway? It is a story we tell each other about who has value and who doesn’t based on their performance on a graded monetary curve determined by governments, politicians, corporations, and human resource managers. It is a fiction created by monarchs 500 years ago when they set out in wooden boats to find treasures in distant lands, kill indigenous populations, enslave others, and exploit free and cheap labour to extract the resources of the land to enrich their own empires.

What is a corporation but a way to reduce risk and liability for owners of capital and financial investors by inventing a fictional entity to absorb legal responsibilities by impersonating a human being. Since the corporation cannot be morally responsible when things go wrong, it can be merely dissolved. It is a front for irresponsible behaviour at a global scale. For corporations, borders are meaningless. It is only humans who are subject to the arbitrary category of citizenship, granted by the nation state.

Case in point: Canada is a corporation, the property of the British Crown. It was once known as the Hudson’s Bay Company. The company sold its land assets to the Dominion of Canada, an experiment in nation-building led by a man who used a railroad as a means to invade Indigenous territory. Canada is a corporation that was a collection of colonies of a monarchy that tried to experiment with nationhood and failed when it could not kill or absorb all the Indigenous Peoples. The corporation claims 97% of the land as Crown land, then tries to run a public relations campaign about how it is trying to reconcile with the people who had previously lived on the land for thousands of years.

The victors write the histories. The people have the power to win over the manipulations of religious institutions, corporations, and governments. We have this opportunity to stop, think, and decide what is worth working for.

How can we gain permission to ask better questions or to think about the bigger picture?

The human scale and experience design

Jacob Pernell, one of my UX Academy students on Designlab, invited me to give a talk at a small meetup in Santa Clara for the UX Wizards of the South Bay on Friday, October 19, 2019. This was part of my presentation.

I attended the Jamstack conference in October of last year, and I was impressed by the community that is building around the concept of decoupling the presentation layer from the data layer.

What I have discovered about designers and developers as we use the design thinking process to solve problems is that innovative thinking tends to be much more difficult than incremental thinking.

We are concerned with the minutiae, especially as our roles within the process become much more specialized as technologies scale and become more complex and organizations become larger and more complex.

My question has often been, who is thinking about the big picture?

My Airbnb hosts in San Francisco are also employees at the Airbnb HQ. Yesterday, they took me for breakfast at the Airbnb HQ and gave me a tour of the building. The idea of creating neighbourhoods for the communities that make up the organization is a way of directly connecting the people creating experiences to the hosts and guests that they are serving. The people who have become part of the Airbnb community have come to see the world in a whole new way by discovering neighbours in different places than the places they call home. In that way, the world has become smaller as we realize that we are all neighbours in a small world. At the same time, the world of opportunities is as vast as the universe. That can be overwhelming for individuals as we consider the limits on our time, energy, and resources.

Imposter Syndrome

One of the issues that keeps coming up in my role as a mentor of UX Academy students at Designlab is the feeling of imposter syndrome.

What is the role of a designer, now that the barriers to entry to the profession may be as little as the cost of the computer and the tools and software to perform the work? From the birth of the desktop publishing revolution to the increased access to information afforded by the global adoption of internet-based communications, the knowledge and experience needed to obtain entrance to the design profession is not only much more available but is being actively sought out by a generation that is being taught the value of design thinking. Apple, having now reached the milestone of achieving $1 trillion dollars in market valuation, has proven that design is big business. Everyone wants to be a designer. We have new roles to which people aspire, such as Chief Design Officer.

The world is a very different place than the one where, as a junior high school student, I discovered that there was a path to make money as an artist, in contrast to the stereotypical path of the “starving artist.” Almost 40 years ago, I learned about a profession known as a “Commercial Artist,” and I dedicated myself to learning everything I could. Our high school provided access to equipment for silk screen printing, photo typesetting, a process camera, a photography dark room, a waxer for mechanical paste up, a letterpress printing press, an offset printing press, and the equipment for exposing and developing metal offset printing plates. Still, as far as I was aware, I was the only person in the high school I attended who graduated with the intention to become a “Graphic Designer.”

Now, as children are being taught human-centred design in school, and as UX and UI design have come to be a highly desirable avenue of pursuit for those who would like to be a part of the technological revolution, those of us who have dedicated our lives to the craft of design are left wondering if we are special anymore.

If everyone is special, no one is special.

The Incredibles is a lesson about what makes us special as human beings. The desire to be special can go to such extremes that we can lose our humanity in the process. As we lament our own imposter syndrome, it is interesting to contrast our own foibles with the extremes demonstrated by the villain of the story, Syndrome. In fact, each of the characters is coming to terms with their own experience of agency in the world, or lack of it.

The first one is when Dash gets in trouble in school; on the car ride home, Dash says, “Our powers make us special,” to which Helen (Mrs. Incredible) says, “Everyone is special, Dash”. Dash retorts back to her, “Which is another way of saying that no one is.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8gXCCBmTvBI

This is not just the opinion of a frustrated little boy, he is parroting the frustrations of his father who later on is arguing that a 4th grade graduation ceremony is silly (in his words, psychotic) because, “They keep celebrating new ways to celebrate mediocrity, but if someone is genuinely exceptional, they shut him down because they don’t want everyone else to feel bad!” And lastly, this theme comes to a head when Syndrome is planning on giving everyone superpowers with his tech and claiming, “When everyone is super, no one will be.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A8I9pYCl9AQ

This movie establishes the fact that there are some people who are exceptional and others who are not. Now, I understand that this is set in a world where some people have superpowers and others do not, but could I say that even in our real world, this is true?

Embrace Your Mutations

Find what makes you weird and celebrate it. At least, that is the lesson that people have learned from their zigzags: that there is no linear path, and you might as well enjoy the journey, learn some things along the way in your search for work that you love.

Alie Ward’s advice, after interviewing several people doing fascinating work and discovering that their paths were never linear, is to “embrace your mutations.” Figure out what makes you weird and unique and discover how that difference can become your advantage.

- ZigZag Podcast: How Valerie Jarrett Turned Her Misery Into Motivation

- 100th Episode: Best Life Advice from Ologists + 100 More Ologies

The Modernist Metanarrative

If we look back over the past 100 years since the beginnings of the Bauhaus school in Weimar, Germany, opened in 1919, we marvel at the accomplishments of painters, artists, and architects to gather and collaborate to fulfill the vision of its founders.

Let us then create a new guild of craftsmen without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist! Together let us desire, conceive, and create the new structure of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.

https://worldhistoryproject.org/1919/walter-gropius-and-bauhaus-period

Rebuilding out of the ashes of the excesses of the past and the political and economic struggles that culminated in what was then known as The Great War (World War I), these Modernists discarded the forms and models of tradition to create a new, modern approach that combined art and technology with the industrial processes of mass production. As the political unrest of Nazi Germany compelled the students and masters of the Bauhaus to shut down the school, many in the diaspora who were able to escape the violent fate of Europe spread their modernist ideals to schools of art, design, and architecture around the world. Concrete, steel and glass became the modern building materials that would dominate the International Style of architecture, and ultimately the skylines of most major cities.

http://www.bauhaus-movement.com/en/

We credit the work of designers such as Dieter Rams as the influence for the ubiquitous minimalist designs of silicon, aluminum and glass that we use every day in our work and communications.

In spite of their age, Braun products designed by Dieter Rams still look modern and they have been recognised as a source of inspiration by Jonathan Ive, Apple’s Chief Design Officer.

The products that Dieter Rams designed for Braun were a collaboration with the Ulm School of Design, co-founded by a former student of the Bauhaus, Max Bill. Thus, we can draw a line of influence from Walter Gropius, the architect of the Bauhaus, to Dieter Rams at Braun, and to Steve Jobs and Jony Ive at Apple.

Postmodernism

The modern century collapsed along with its modernist ideals and the metanarrative of an artistic and technological utopia with the fall of the World Trade Center. The building embodied a vision of the unity of democracy, technology, capitalism, and globalism that would “one day rise toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.” That faith has been in a process of deconstruction ever since, and the postmodern age has yet to determine what, if anything, we should build in its place. The building itself has been replaced, but the core tenets of the faith are in question, and the current political crisis of leadership merely signals the weak foundations of a crumbling nationalist political empire that is quickly being replaced by a global, corporate capitalism, far beyond the constraints of democratic appeals. These hierarchies, representing the largest technology corporations in the world, have assumed dominance over the networks through economic supremacy. As designers, we must take responsibility for the idols we have created in service of big data, key performance indicators, targeted marketing campaigns, and the attention economy. We have learned the language of business, marketing and data science, but have lost our humanity in a Faustian bargain, choosing to focus on present gain without considering the long term consequences. We face a dilemma if we bite the hand that feeds us.

The success of the combustion engine is a case in point. Designers rallied around auto manufacturers to cash in on the design, advertising, and marketing profits of a business that suppressed the more desirable, feasible, and viable electric alternatives to buttress their own supremacy over the market. The success of the automobile promoted urban and suburban development, and economic, political, and military infrastructure that undermines community and destabilizes international diplomatic relationships, creating such a dependence on scarce and depleting resources that we can no longer imagine living without these technological conveniences. Similarly, we are addicted to devices that tend to create lonely, depressed, and anxious people.

Others would go as far to say that social media is ripping society apart.

https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/11/16761016/former-facebook-exec-ripping-apart-society

Can we design our way out of this? Or is design the problem?

Questioning Orthodoxy

Something interesting is happening in religious and spiritual circles that is an interesting analogy of the problems that people are facing in business and politics. Postmodernism is a movement away from the metanarratives of modernism. The term itself is a negation of the previous movement without suggesting an alternative.

Similarly, there is a phenomenon that is referred to as the “nones.” These are the people who would check the box labelled “none” in regard to the question of affiliation to a religious community. What these people have in common is not a rejection of spirituality, necessarily, but a rejection of the hypocrisy of a self-serving religious hierarchy that hypocritically props up the status quo by actively supporting the existing orthodoxies and hierarchical structures while claiming to represent a polemical leader who was known for offering good news for the poor and the oppressed. These religions of fear have been exposed as hollow, since they merely mask the intentions of its leaders and followers to seek their own personal security and prosperity.

The “nones” describe their nomadic search for hope and signs of life as a form of deconstruction. Their teachers describe a process of three phases: construction, deconstruction, and reconstruction. They realize that they have been handed an orthodoxy by the people in the religious communities from which they came that does not actually square with reality. While their view of the world has been constructed through their relationships with these people in their community, they have come to question the very foundations of their beliefs. The are setting out on a journey through the desert by deconstructing inherited dogmas and orthodoxies, and by investigating the latest scholarship and experiments. Then, leaving behind the traditional communities, they are finding relationships, communities, and ways of living that renew their sense of humanity, connection, and belonging. They are reconstructing their personal life, their relationships, and entire communities by reconnecting with people and with the natural world.

In a sense, the design community is discovering their own complicity in propping up corporate and capitalistic hierarchies that are increasing inequities, maintaining oppressive workplaces, and limiting opportunities for learning, collaboration, autonomy, and creativity. They may be personally experiencing the opposite, but the reality for those who are not part of the commercial, technological and creative classes is that they are finding themselves displaced by technologies that provide no alternatives for finding work that can meet basic human needs, let alone work that is meaningful and rewarding.

How, then, shall we live, given our growing awareness of the situation in which we find ourselves? We are complicit in a hierarchy that we ourselves have created. To question democracy, capitalism, technology, and globalism is to question the orthodoxies that we have been handed, the very foundations on which design, as a profession, have been established, and that we have been tasked to preserve and herald. The role of the priest is to serve the monarch, maintaining the royal records and histories and disseminating information to the people as deemed appropriate by the monarch and the royal advisors. If we are found to have questions regarding the foundations of the kingdom or empire, we shall lose our role and status, and possibly our heads. We face an existential question, to resist and face the consequences of what we ourselves have wrought, along with the implications of refusing to no longer be complicit in the workings of the machine, or to passively accept our lot in life and carry on.

The Whistle Blowers

Ruined by Design

Mike Monteiro is outspoken about the ethical responsibilities of designers.

The combustion engine which is destroying our planet’s atmosphere and rapidly making it inhospitable is working exactly as we designed it. Guns, which lead to so much death, work exactly as they’re designed to work. And every time we “improve” their design, they get better at killing. Facebook’s privacy settings, which have outed gay teens to their conservative parents, are working exactly as designed. Their “real names” initiative, which makes it easier for stalkers to re-find their victims, is working exactly as designed. Twitter’s toxicity and lack of civil discourse is working exactly as it’s designed to work.

The world is working exactly as designed. And it’s not working very well. Which means we need to do a better job of designing it. Design is a craft with an amazing amount of power. The power to choose. The power to influence. As designers, we need to see ourselves as gatekeepers of what we are bringing into the world, and what we choose not to bring into the world. Design is a craft with responsibility. The responsibility to help create a better world for all.

The Attention Merchants

An information system that relies on advertising was not born with the Internet. But social media platforms have taken it to an entirely new level, becoming a major force in how we make sense of ourselves and the world around us. Columbia law professor Tim Wu, author of The Attention Merchants and The Curse of Bigness, takes us through the birth of the eyeball-centric news model and ensuing boom of yellow journalism, to the backlash that rallied journalists and citizens around creating industry ethics and standards.

“When I read the history, there is this important role played by people like yourselves who sound the alarm. There are many examples, frankly, of advocates and concerned citizens who say, you know, something is going on here that isn't quite right.”

Changing our Climate of Denial

Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin was in conversation with Anthony Leiserowitz, Director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

Tristan Harris: I'm someone who’s highly climate interested, so my newsfeed, at least up until the coronavirus, is actually post after post after post of climate-related news. But what kind of news is it? It’s basically learned helplessness. It’s basically this is: “It’s worse than you thought, and there’s nothing you can do.”

…

Anthony Leiserowitz: Yeah, so look this is absolutely vitally important that you build in some kind of feedback mechanism that helps people understand that they're part of something bigger than themselves. And that’s like one of the core human drives, is that we actually don’t want to be an isolated, lonely individual that only succeeds on our own. Most people want to be want their lives to have meaning, I get this brief flicker, candle flicker of life in the grand scheme of things. What did it add up to? What was the value of your life? People want to know that they’re contributing to something much bigger than themselves and, you know, for many people it’s their family, but for many people it’s beyond that.

And so this is, I'll just use a very great historical example, we need what are called Cathedral projects. Okay, if you go back into medieval times, you know communities back in, say, medieval Europe would start these grand projects to build these glorious cathedrals to glorify, and honor the divine. And they knew when they started these giant projects that they were never going to live to see the outcome. These were projects that were going to take 100 plus years to actually build, but they believed in the vision, and they, more importantly, they could see what they had done. “I laid that set of stones right there,” as you’re watching this building starting to emerge from nothing. Okay. And you could take enormous pride as part of your community that you were helping to build something that was going to outlive you and everyone in that community. It would be standing there for generations to come. That was true in the medieval period. I think we still are driven for those kinds of projects today.

Tristan Harris: And there is such a rare opportunity because the entire world is experiencing this all together and we're all feeling this kind of solidarity all together, and if you know the prime directive is know your audience. The entire world is feeling solidarity. This is the audience for the time to build something really great. This is one of the very rare once in 100 year type occasions where the psychology of the world is ready for something.

Grief

Dr. Hillary McBride is a Vancouver-based therapist, researcher, speaker and feminist writer, who is making psychology and empirical research more accessible.

In the Grief episode of The Liturgists podcast, Hillary McBride responds to William Matthew’s observation, based on the ideas of René Girard about scapegoats in religions as an evolutionary response to pain — to social anxiety and guilt. She responds to the idea that problematic behaviours arise from grief, from pain that we haven’t dealt with appropriately.

I wish that we could all make assumptions that this is all grief. Instead of being angry at the person for butting in line, or cutting us off in traffic, or not calling us back, or saying something hurtful, we could assume that it’s all just pain trying to make its way out of us.

How can we better understand the stories we tell ourselves and, perhaps, tell better stories?

Eric Holthaus

In order to change the world, we first have to believe it's possible. We need to tell stories about a better world we all deserve.

This is my story of what will happen in the 2020s.

This is what it will look and feel like when we win back our future.

https://twitter.com/EricHolthaus/status/1214885983898021888

Our identities are formed by the stories we tell ourselves

We learn language to connect to the complex interactions of a socially, economically, politically, and ecologically interdependent world of relationships. We share memories, stories, and experiences, as well as a collective imagination of what the future could look like.

The 20th-century economists told us a story about who we are, based on John Stuart Mill’s persona of "Rational Economic Man" as purely self-interested, with little regard for the interests of others. “This value in self-interest and competition over collaboration and altruism, this model remakes us. It’s incredibly important how we how we represent ourselves. It changes us.”

Kate Raworth argues that rethinking economics can save our planet

Endless growth may actually be hurting our economy -- and our planet. Economist Kate Raworth makes a case for "doughnut economics": an alternative way to look at the economic systems ruling our societies and imagine a sustainable future for all.

Canary in a Coal Mine

Sometimes it is not possible to see what threatens our survival. Coal miners would descend into the depths of the earth with canaries in bird cages.

If dangerous gases such as carbon monoxide collected in the mine, the gases would kill the canary before killing the miners, thus providing a warning to exit the tunnels immediately.

We depend on authorities who are experts in epidemiology and medicine to understand the dangers of a viral pandemic, since we cannot see the threat.

Global Climate Strike

On September 28, I joined the Global Climate Strike in Vancouver. Here is the sign I designed for the protest.

This article sums up the basic idea about how we need to change the narrative that we have accepted about the way things are, if we are committed to moving beyond the status quo.

This podcast is about the story of money. It is fascinating how it is just a fiction, a story that we have told ourselves about what is valuable.

Or, as Greta Thunberg might put it, they are “fairy tales of eternal economic growth.”

A Design Challenge

“How do we more fully recognize each other as human, in order to be more humane? And how do we shift what we talk about as political questions to ethical questions, which is really where they belong?”

Posted by Stephen Bau on Twitter

Redesigning Education

Working with Designlab, for me, is a part of the process of engaging in the design challenge to move beyond the status quo: redesigning education.

A System of Systems

I recently took a course with the Buckminster Fuller Institute. The BFI course was built around four video discussions: David McConville on Gaian systems, Tom Chi on Rapid prototyping, Ganga Devi Braun on ecology, and Daniel Schmachtenberger on sense-making.

Sense-Making

When we explored sense making with Daniel Schmachtenberger, he talked about how we often reduce our cognitive load by outsourcing our sense-making to trusted authorities. However, hierarchies exist to perpetuate the status quo, to be the gatekeepers of tradition. This becomes a problem when, as Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs reveal in the documentary film, Planet of the Humans, the global corporate culture is engaged in a misinformation campaign to manipulate our destructive consumption habits to maintain and grow revenues.

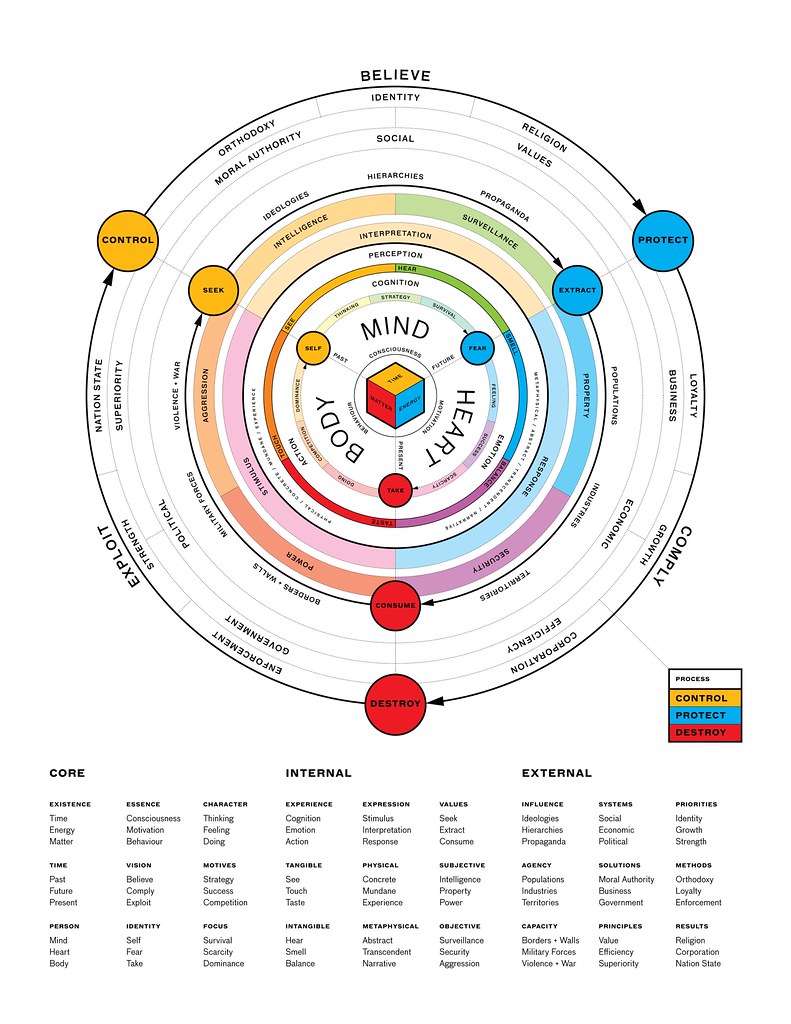

Mental Models for Human Experience: Understanding Human Values, Perceptions, and Behaviours

The conversation about design is evolving as the scope of design expands from physical artifacts to living systems. Increasingly, we are exploring ideas about organizational transformation and social change. In other words, we are expanding the scope of design from the physical to the metaphysical: to the social, the economic, and the political. These are issues of connection, capacity, and power.

Design as a Catalyst for Change

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

— R. Buckminster Fuller

The Design Challenge

The challenge, then, becomes more about how to understand the values, perceptions, and behaviours of the individuals who make up an organization or a society. Through brain research and cognitive science, we are coming to understand that we are not actually rational creatures. Rather we react and behave emotionally and invent rationalizations to justify our instinctive and impulsive actions.

Values, perceptions, narratives, and social identities are far more compelling than data, facts, information, and rational thought in the way that we understand our environment and make decisions as social creatures.

Story 1: Collaboration

How, then, can we begin to map the human experience? How we can design mental habits, social systems, and physical environments for resilience and symbiosis with the living processes and ecology that are the foundation of our biological support systems?

To better understand our materials as experience designers, we need more holistic mental models of the human experience, as a way to understand what we are designing for.

- Mental Models

- Mental Models for Human Experience: Understanding Human Values, Perceptions, and Behaviours

Story 2: Competition

The primitive limbic systems in our brains are designed to trigger the fight or flight response as a matter of survival in a world of physical threats. Senses are attuned to dangers in the environment and events perceived as threats will automatically trigger a physical and biological response of increased heart rate, a release of adrenalin, and a heightened state of awareness, along with emotions of anxiety, fear, and panic.

When this intellectual, emotional, and physical state of anxiety is prolonged, we call this stress. People who live in this constant state of fear and scarcity will tend to engage in behaviours that are focused on survival and self-preservation. This interpretation of constant threat leads to isolation and aggression, as members of a group engage in a competition for scarce resources and demonstrations of strength and dominance to control the group, protect resources, and destroy enemies. However, such isolation and aggression has a tendency to undermine the survival of the group.

Rapid Prototyping

In a conversation with Tom Chi, board chair of the Buckminster Fuller Institute and founding member of Google X, Amanda Joy Ravenhill asked the question, “How can we use rapid prototyping to make sense of the world around us?” Tom Chi described his practice called, Rapid Prototyping.

…we create models or frameworks which are abstractions of the real world. They help us to set parameters and get perspectives on the world in front of us.

Rapid prototyping is pretty different than all of those things. It basically doesn’t presume that there’s any deep fundamental model at the outset. It doesn’t mean that you won’t discover a model in the process, but it’s built off of something that I call hyper-empiricism, which is, “It is because it is, and it works because it works.” And the way that you figure out whether a thing will work is you keep trying it until it works.

…

A lot of people have got a lot of meetings. If you go sit in on the meetings and you watch how the meetings are taking place, most people are discussing the topic at hand using conjectures. And this is no more complicated a concept than just saying it’s a guess that you have about what might happen in the future.

…

Now, if you understand that conjectures are very likely to be incorrect, you’ll see that the entire exercise that we’re doing at work—about 90% of the work that I see in most workplaces—is just wasted time. And that’s one of the places where you can get more rapid. Just, first off, stop wasting 90% of your time.

The way that you figure out whether a thing will work is to keep trying it until it works. (3:03)

How do we prototype for resilience? How do we imagine, design, and build the future together?

We have learned over the years to create stories to entertain, thrill, and amuse people over the years.

Brett Frischmann refers to our storytelling abilities as special powers.

Human beings have special powers. We can imagine things that don't exist, then communicate with each other in person at a distance and across time about imagined things. These powers are what allow us to develop shared culture, beliefs, laws, technologies, and all the other things that are essential to cooperation and modern civilization. What matters most is how we exercise those powers across generations to shape our world, and ourselves. This is how we engineer humanity. We've been doing it since the invention of tools for a millennia. And so the big idea I think that we've engineered for ourselves since the enlightenment—certainly over the past few centuries—is the belief that, despite the many environmental contingencies that are outside of our control that shape who we are and what's possible for us, we nonetheless can be authors of our own lives. We can imagine a future for ourselves and try to get there. Same thing for our children. Same thing for future generations. We have some meaningful agency or degree of freedom in our lives, but this freedom is not naturally given. It's not inevitable. It is contingent. It can be taken. It can be lost. We can be drones. This is important. It depends on the world we build.

New Paths

Is the choice so clear cut? There are some who are clearing alternative paths through uncharted territory. The public benefit corporation is one option. Humane technology is another. Social capital is an investment in a mission to harness technology to address core human needs, to drive a bottom-up redistribution of power, capital and opportunity. The blockchain is an attempt to build a trust protocol. Still others are reinterpreting the role of the designer and finding ways to give their work away for free as a way to disrupt the status quo and create new models of impact. A new economy is emerging based on diversity, ecology, and sharing. By observing people and how they interact, we hope to apply what we learn to making cities for people designed for the human scale. The challenge is to create living buildings, alive with human activity designed to integrate harmoniously with the living systems all around us.

Builders Collective

The builders collective is an idea conceived as something akin to a revival of the Bauhaus movement, combining art, design, architecture, theatre, and urban planning. However, the building materials have changed from glass, steel and concrete to perception, cognition, emotion and action, as Jesse James Garrett would express the new context for experience design: design for engagement.

The concept of designing for engagement in combination with the recognition of the unintended consequences of design now leads us toward a movement to realign technology with humanity’s best interests, for humane technology.

What we have in mind is real world experience that combines the concepts of empathy and resilience, to reimagine our social architecture.

Design for resilience starts with the assumption that things will go wrong, and engages in a process of anticipating the unintended consequences (e.g. the internal combustion engine leading to global climate change) through observation (watching, listening) to build empathy, and finds inspiration from nature to solve challenging problems.

The thought, then, is to extend the realm of design from questions of “how" to the deeper questions of “what" and “why.”

For that purpose, we gather as artists, creatives and innovators to build our future on the foundation of senses (perception), minds (cognition), hearts (emotion) and bodies (action) that have been reoriented to the truth about life in our present reality. We are no longer designing the physical artifact, but we are designing the human experience. This is something that cannot be left to governments and corporations, the most inhuman of human inventions. This is a project for humanity as a whole as we envision life as part of an interconnected and interdependent ecosystem on this earth.

Reimagining the Role of Design

We have together built a machine into a form that reflects the fragmented and siloed intellectual disciplines that we model after educational institutions, corporate organizational structures, and political systems that divide our thinking and work into discrete categories and disciplines.

The design challenge of our time is to create a new synthesis that arises out of our growing understanding of the failure of an atomized and individualistic conception of the self that is fuelling the global identity crisis. Belonging and identity have become central to an arms race of propaganda and competing narratives of reality.

Diversity and multidisciplinary work are the best models we have for our survival and for the continued flourishing of the human species.

We are caught in a dialectic of opposing forces, in the politics of thesis and antithesis, right versus left. We need a new synthesis that transcends the old paradigms. Unity in diversity is the model for both the organism and the planet.

The future of design and architecture may be in the integration of the separate disciplines to learn how interconnected systems work and model the built environment to imitate the processes of living organisms.

Physics and biology are the basis for a new movement in engineering and design called biomimicry. By modelling architecture after biology, we can create living systems that can live in harmony with each other and the natural environment, in a symbiotic relationship with the earth rather than parasitic.

Metaphysical Design

As design is evolving from the physical artifact to living systems, we need the permission to engage in the language of the metaphysical, by which I mean the social, economic, and political.

Maybe, after millennia of design iterations, we need to rest and contemplate what we have created and reimagine a social architecture that is not about anthropocentrism and human-centred design, but on earth-centred symbiosis with the interconnected living systems of the planet.

Design systems are not limited to visual and typographic guidelines for screen-based technologies. We are living on a planet that is on fire because of human activity that is destroying the only life support system that we know of in this universe.

To get back to basic design principles, we need to reframe our problem by first answering the question, How might we find a way to live together without destroying each other?

In the effort to build leaders to design a resilient society, we need a builders collective who are thinking through our most pressing design challenges to realize the kind of world we actuality want to live in. This means thinking about the effects of exponential change as we face the reality of the social arc, the curve that describes our trajectory as a species, in terms of population growth and consumption of the finite resources of the planet. To do so will centre our discussions around ideas for social organization that align with what we are finding works best in engaging the best of what it means to be human, to value humans far beyond the fictions we tell ourselves about capital, corporations, and nation states. This will mean reimagining our social architecture by learning from our failures.

Design for Resilience

Given the challenge our generation faces, we endeavour to invest time, energy and resources in the effort of building leaders to design a resilient society. By considering basic human needs of food, clothing, and shelter, we are reimagining the metaphysical environment: the social, economic, and political. How might we build a new economy on a foundation of resilience and symbiosis?

By creating greater self-awareness, we may recognize how things can go very wrong and create virtual models with predictive power to anticipate problems before they become reality. This is a collaborative project to better understand ourselves and our place in this world, to find generative ways to live with each other and the natural world.

Transcending human-centered design, this is design that seeks to learn from nature, to put into practice the knowledge and principles of biomimicry to reimagine and redesign our environment, to reconnect ourselves to our own humanity and to reconnect us to the earth and all living things.

We need to think like architects about the social, economic, and political implications of what we are doing.

- Social: does it meet a human need?

- Economic: given what is possible, can we use the available time, energy, and resources to accomplish it?

- Political: can we convince other people that it is important and valuable to invest in this course of action?

This is metaphysical design. These are the intangibles that we cannot reduce to measurements. We must decide what we value, and there are no physical, empirical methods for discovering these things, unless we reduce people to numbers, which is what capitalism does to humans. Humans are merely numbers on a balance sheet.

Builders Collective

To become a resilient society, we need to become the heroes and protagonists of a different story.

Who are we? We are a builders collective. We are building resilience, relationships, and community. We are building leaders to design a resilient society.

Exploring how we can imagine, design, and build the future together. We are documenting the work of a creative collaborative community with a focus on reimagining, redesigning, and rebuilding our social architecture.

Resilience Through Design

Thank you to everyone who joined our national “Resilience through Design” a few weeks ago. More than 200 participants joined our call to share ideas, outline challenges and opportunities, and highlight community initiatives.

The SD Canada team has reviewed your comments and consolidated all contributions here. We are committed to supporting the Canadian Service Design community through the following immediate next steps:

Promote calls for volunteers from organizations and individuals seeking immediate design & strategy help. If you would like to offer your skills in service design & strategy, see below for opportunities. If you are seeking service design & strategy help and would like us to promote your opportunity, please hit reply on this email.

Continue the conversation in more focused and interactive calls. The team has outlined three broad topics that surfaced multiple times during the original call. We will be organising follow-up conversations on the following topics. Your invitation to register for these calls will be sent in next week's newsletter.

- Equitable Access To Services

- Overcoming Bureaucracy

- Balancing Speed + Quality

Notes

- Wikipedia: Monarchy of Germany

- Wikipedia: Bauhaus

- Wikipedia: Dessau

- History: Spanish Flu

- History: Why World War I Ended With an Armistice Instead of a Surrender

- Judith Rodin: The Resilience Dividend: Being Strong in a World Where Things Go Wrong

- Judith Rodin on Resilient Cities

- Mike Monteiro: Ruined by Design

- Rebecca Solnit: Falling Together

- Tristan Harris: Climate of Denial

- Anand Giridharadas: Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

- Hillary McBride: Grief

- Michael Moore and Jeff Gibbs: Planet of the Humans

- Daniel Schmachtenberger: The War on Sensemaking

- Amy Westervelt: The Father of Public Relations

- Shoshana Zuboff: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

- The Daily: The Glut of Oil

- Chris Hedges: American Fascists

- Louis Hyman: Temp: The Real Story of What Happened to Your Salary, Benefits, and Job Security

- “How to Hide an Empire”: Daniel Immerwahr on the History of the Greater United States

- Free will under threat: How humans are at risk of becoming wards of technologists

- Re-Engineering Humanity: Brett Frischmann (Part One)

- The Magic and Logic of Color: How Josef Albers Revolutionized Visual Culture and the Art of Seeing

- What Josef Albers Taught at Black Mountain College, and What Black Mountain College Taught Albers

- The Josef & Anni Albers Foundation

- Anthony Leiserowitz, Senior Research Scientist and Director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication (YPCCC)

- Artists as “the Antennae of the Race”

- Weimar Republic

- Full Faith & Credit

Resources

Livestorm Webinar

Learn how to design for resilience with Designlab Mentor Stephen Bau.

In the session, you’ll learn:

- What resilience is and why a designer needs to be resilient

- How we can all imagine, design, and build the future together

- How you can ask better questions while keeping the big picture in mind

- How to prototype for resilience and tell better stories to illustrate resilience

https://app.livestorm.co/designlab/design-for-resilience-with-stephen-bau